Reviews and Ratings of Small to Medium Sized Enterprises Usa

Small and Medium-Sized Enterprises (SMEs): The Engine of Economic Growth through Investments and Innovation

i

Department of Finance, The Bucharest University of Economic Studies, half-dozen Piata Romana, 010374 Bucharest, Romania

ii

Department of Information science, Statistics and Mathematics, Schoolhouse of Computer Scientific discipline for Business Management, Romanian-American Academy, 1B Expozitiei Blvd, 1st District, 012101 Bucharest, Romania

3

Doctoral School of Sociology, Academy of Bucharest, 36-46 Mihail Kogălniceanu Blvd, 050107 Bucharest, Romania

*

Author to whom correspondence should be addressed.

Received: sixteen November 2019 / Revised: sixteen December 2019 / Accustomed: 23 December 2019 / Published: ane January 2020

Abstract

Minor and medium-sized enterprises (SMEs) are crucial for local economic development, playing a noteworthy role in job creation, poverty alleviation and economic growth, just they encounter many funding barriers. The purpose of the current paper is to investigate the bear upon of investments and innovation on territorial economical growth, as measured by turnover, for Romanaian active enterprises, especially SMEs, over the menses 2009–2017. By estimating several log–log linear regressions, the quantitative outcomes provide support for a positive influence of investments on turnover. The clan was confirmed both for all agile enterprises at the national level, too as for micro, pocket-sized, center-sized and big companies. Every bit regards expenditures on innovation, a positive impact on turnover was best-selling for all enterprises and especially for big companies, just at that place was an absence of any statistically significant relation in the example of SMEs. The impact of firm size on turnover was positive for all agile enterprises at the national level, along with active micro-units. Besides, the estimation results show a positive impact of the number of active micro-units on territorial economical growth. The empirical findings are relevant to managers and policymakers in order to stimulate, encourage and offer back up to SMEs' evolution through their strategies.

ane. Introduction

Small and medium enterprises (SMEs) are a noteworthy driver of economic evolution [1], beingness vital to well-nigh economies across the world, particularly in developing and emerging nations [2]. They represent 99% of all businesses in the European Marriage (EU) and in the terminal five years, provided about 85% of new jobs, also ensuring 2-thirds of the total private sector date in the region [3]. For case, in 2015, at that place were most 23 1000000 SMEs that provided 90 1000000 jobs, generating a higher added value of 3.9 billion EUR [iv]. Dissimilar to big corporations, SMEs are highly flexible, revealing a superior flexibility to technical shifts, higher promotion of income distribution and improve adaptability to fluctuations in the market and new customer requirements, while their organizational construction allows for quicker decision making [5]. Nevertheless, to achieve this potential, SMEs need a continued source of longstanding funding so equally to invest in growth opportunities [6]. Hence, wishing to strengthen the entrepreneurial spirit in Europe and to create weather for the practical evolution of innovative concepts, the European Commission designed a set of measures alongside a modern and coherent policy for SMEs. The master purpose of this plan is to support the growth and development of SMEs in close relation to the employment market place [seven]. SMEs are viewed as the backbone of an economy [8] since they exert a pregnant function in lessening poverty, employment creation, strange trade promotion and technique innovation [9], also contributing meaningfully to the growth of developing economies [10]. And then, the strategy adopted in 2008 for Europe via the "Small Business Act" considers the awarding of the principle "Offset, call back at a small scale" [11] regarding the adoption of policies, regulations and policy measures that should offer support to the needs of SMEs. Since 2010, the European Parliament has adopted a series of resolutions, such every bit: community policy to stimulate innovation through European SMEs [12], industrial policy for globalization conditions [thirteen], the competitiveness event and the issue of business organisation opportunities in the European Union [14], the re-industrialization of the economy to provide competitiveness and sustainability [15], supporting information and communications applied science (ICT) evolution regarding the transition towards a blazon of sustainable economic system and the resolution of social and ecological problems mentioned in the European Strategy 2020 [16], easy access for SMEs towards financing possibilities [17] and the stimulation of research/development and innovation processes offered by the research plan Horizon 2020 [18,19]. Thus, through European and national policies, and through start-up financing programs or business organization incubators, SMEs have been encouraged and stimulated to develop, grow and support the economy and local, regional and national activities inside communities.

Since markets have go gradually more competitive, SMEs effort to affirm themselves via new product advances in order to compete with large enterprises. Hence, innovation plays a fundamental role in accomplishing competitive power [20], beingness oriented towards novel products, original marketing and management methods, too as genuine technologies [21]. The model of Porter [22,23] promotes the thought that enterprises vest to a greater globalization and internationalization procedure. Competitive advantage is created and supported locally within a national or regional surface area, each having its own economical or cultural characteristics. The European Commission defines a competitive region as i that is able to "ensure both the number and the quality of jobs" [24]. Regarding this description, the gross domestic product (GDP)/inhabitant is considered to be a proper representation. It tin can exist deconstructed into more components with precise economic interpretations [25].

The idiom "regional competitiveness" is a phrase that refers neither to macroeconomy nor to microeconomy because regions can be considered neither simple accumulations of enterprises from a sure area, nor reductions of a certain nation to a smaller calibration. Therefore, it tin exist considered that the regional level is much more complex and challenging to analyze. Regions are in direct competition with each other for the conquest of markets and for alluring investments [26]. Hence, 1 region may possess absolute competitive advantages if these include technological and social factors concerning infrastructure or superior institutional factors compared with other regions, which are external to enterprises, but which contribute to their evolution and greater success.

This paper aims to investigate the role of agile enterprises, peculiarly SMEs, in territorial development in Romania, every bit measured by their turnover. Previous studies on SMEs' access to finance and their innovative capacity have focused on various states such as Republic of albania [27], Brazil [28], Poland [29,30,31,32], Romania [21,33,34,35,36,37,38], Spain [5,39], Malaysia [40], Eye Eastern and Central Asian states [41], Nigeria [1], Portugal [42], United States [43], Vietnam [44] and Republic of zimbabwe [45]. Nevertheless, preceding research for the Romanian example has focused on topics such as the involvement of SMEs in economic growth [38], the function of SMEs in improving employment [37], SMEs' financing options [36], the influence of globalization on SMEs [35], the sustainability of SMEs [33] as well every bit their importance [34] or innovative capacity [21]. Our research contributes to the existing literature in a number of means. First, we focus on SMEs in the context of an upper-middle-income nation. The fruitful development of central and eastern European nations from planned economies to market place-oriented economies would not have been feasible without the enlarged number of SMEs [xxx]. Studies of this type are rare due to the predilection for exploring firms that are larger, more productive and more than capital intensive [44]. However, another particularity is that well-nigh developing markets feature a depository financial institution-based formal financial system with frail disinterestedness and debt markets [46], alongside a lack of innovation management feel and state-of-the-art engineering [47]. Due to the inheritances of central planning, the growth of SMEs is severely inhibited by their restricted admission to finance [48]. 2nd, the newspaper advances the literature by providing empirical bear witness for the affect of investments and expenditures related to innovation on territorial development in Romania, which to the best of our noesis has not been explored previously.

The paper is structured every bit follows. Section two examines the previous literature and establishes the research hypotheses, while Section 3 is dedicated to the empirical framework. Section 4 outlines and discusses the quantitative outcomes. The last section provides final remarks and policy implications.

two. Theoretical Backgrounds, Literature Review and Hypotheses Evolution

2.1. Prior Research on SMEs Financing

SMEs play an ever more imperative function towards market evolution locally and overseas, influencing sustainable growth in the trading, production and service areas via attracting investments [31]. Co-ordinate to Kersten, et al. [49], SMEs funding plans reveals a positive significant effect on the total volume of financing and/or investment, firm performance and employment. With reference to the theories that enlighten the factors driving business firm investment, the acceleration principle theory [50] postulates that companies increment their investments during satisfactory stages of economical growth, whilst investments are reduced during economic recession. According to neoclassical theory [51], firms increase investment if sales increase, merely investment diminishes if sales fall.

SMEs are oriented towards profit maximization rather than expansion since their legal status is usually proprietorship or partnership, these companies existence ruled by the resolutions of owners. Owners employ their own assets to fund their businesses, because profits more than vital than investments [52]. Wellalage and Fernandez [46] documented that having formal finance is positively related to firm-level product innovation and procedure innovation. Nevertheless, SMEs are challenged with serious financial limitations when compared to listed firms since they cannot increase funds by issuing stocks and bonds, thus bank borrowing is the core source of funding [53]. Besides, scarce collateral, weak solvency, short/no credit history, young bank-borrower dealings, high transaction costs and information asymmetry were noticed as the chief difficulties with reference to gathering commercial bank financing, peculiarly long-term borrowings [43]. Wang [54] exhibited the most significant impediments observed past SMEs managers, namely "access to finance", "tax rate", "competition", "electricity" and "political factors".

Ullah [48] noticed that SMEs encounter lesser financial restraints in nations with higher levels of Gdp per capita, stock market place development, legal systems and property rights, as well reduced levels of corruption. Motta and Sharma [28] confirmed that firm size may affect admission to capital in the hospitality SME sector as small-scale-sized companies may not own high-quality projects required to acquire banking company credits from financial intermediaries. In this vein, Jackowicz and Kozlowski [32] proposed that social ties amongst SMEs managers and bank employees may enhance SMEs' access to banking company financing and rouse their investments.

Hypothesis1a.

The turnover of all agile enterprises at the national level is determined by the investments performed past these firms and their numbers of employees.

Hypothesis1b.

The turnover of all agile companies at the national level is driven by the gross investments performed past these enterprises.

Hypothesis1c.

The turnover of all active firms at the national level is determined by the gross investments performed by these companies, investigated according to business size.

Hypothesis1d.

The turnover of all the micro-enterprises at the national level is driven past the net investments performed past these companies, the number of active micro-units and the number of employees.

2.2. Previous Studies on Innovation in SMEs

In a globalized era—a society based on cognition, respectively—the SMEs reveal exclusive competitive returns on the force of flexibility and quick adaptation to the new requirements of production and global market, exposure to new industrial know-hows [55,56], the ability to place and to apply the value of novel external information [57], the power to chop-chop adopt the modern techniques and technologies for new business models [58], the rapid decision and the lack of bureaucracy in the process of implementing new products and innovative processes [59]. As such, a crucial part in shaping a competitive benefit is revealed by innovation [29]. Exposito and Sanchis-Llopis [39] noticed that innovation of any type (product, procedure and/or organizational) positively influences financial and operational extents of SME operation. Besides, The Organization for Economic Co-operation and Development (OECD) [60] reinforced that college levels of firms' investment in innovation determine higher innovation sales and productivity.

The competitiveness regarding a company refers to "the chapters of producing proper appurtenances and services of eligible quality, at the right price and at the right time" [61] or "the chapters of companies to compete, to develop and to increase profits" [62]. Besides, competitiveness is viewed equally the "dynamic part that depends on progress, innovation and on the ability to self-alter and improve" [23]. Through his pattern, Porter [23] reinforces the thought that, even if the product of globalization takes place forth with the commercial changes, the competitive reward is created and supported through a local process. The national or regional area is the one which, through its economic, cultural or institutional propriety, allows the development of certain economical activities, of specific undergrowth or branches of activity or not.

Along with the industrial development and the improvement in the knowledge social club, the usage of knowledge had get the new economic of import resources, which changes the approach towards operation and competitiveness completely. The company's resources back up its competitive advantage [63], and the manager must nowadays analyze the production along with its social concerns, labor conditions and the value of the local consumption [64]. A new capability of the entrepreneur regarding the concern success is emphasized, regarding the social competence [65], and the advice mode with the providers and the clients, the promoting strategy and the usage of proper visual symbols [66].

The practice strategy has proven that inside ane company competitiveness often requires a long learning procedure which, at the local level tin can be attained through a common effort of all the universities, inquiry institutions, investors and entrepreneurs past creating and developing certain powerful networks [67] with the purpose of reinforcing some new technologies and by creating some business incubators [68] that might back up the local innovation process. All the same, competitiveness will exist emphasized not but by quality and performance, simply also by the plentiful processes inside the company. Amongst these types of processes, the managerial ones are really imperative. Thus, there are studies [69] that prove that the management of SMEs, having solid positions on the marketplace, usually make more than bourgeois choices of disengagement resources, in order to preserve and strengthen the actual turn a profit. The experience accumulated on the market place and the market feedback is required to build a strategy appropriate to local conditions.

Innovation represents the process of placing a certain production on the marketplace (goods or services), a new ane or a significantly improved one. Innovation focuses on the cooperation between research and industry, due to the demand for finalizing the research through practical results related to the technical and technological developments. In Romania, innovation is divers [lxx] as being both a process and a product: "innovation—every bit a product—represents a new function, or the comeback or a broader function of a certain product, process or service, in any domain, which can or could exist available to the demand on the market place, which may or might generate a new type of market; innovation—every bit a procedure—represents the activeness that allows the occurrence of innovation. Innovation—as a process—includes the connectedness between research and development". To all the to a higher place mentioned, typically, the marketing innovation and the organizational innovation can exist added, offering extremely more development opportunities, that allow the usage of high technologies and modern advisory technologies for structure and management. Besides, OECD [71] defines iv types of innovation, namely "product innovation—the introduction of a proficient or service that is new or significantly improved with respect to its characteristics or intended uses; process innovation—the implementation of a new or significantly improved production or commitment method; marketing innovation—the implementation of a new marketing method involving pregnant changes in product design or packaging, production placement, production promotion or pricing; organizational innovation—the implementation of a new organizational method in the business firm's business practices, workplace organization or external relations". Saridakis, et al. [72] differentiate amid radical innovation defined as progression in knowledge due to the advance of novel products and processes that are new to the market/industry and incremental innovation defined equally an unremitting enhancement to products, processes or services that are novel to the firm just.

The practice has shown that the innovation process of a certain product, service or new performant technology is inseparably connected to intense research-development activity inside companies, among universities, inquiry institutions and other research entities, experts or scientists within all domains. By usually working on partnerships for different well-defined projects, implemented and monitored, these communities include the best professionals in the domain, man resources with high qualifications and outcomes in the fields, integrated into real scientific communities and able to reach the best performance. Globalization, the virtual, extremely dynamic marketplace, the technological development, the computerization and the quick digitization determine the involvement of these communities even more within economy, social and cultural life at the national and regional level. This is the only mode to withdraw the major differences between nations and regions and amid companies. As such, the EU determines the general policy, accepted by all the participating countries, of allocating the amount of 3% of GDP for the activities performed in the inquiry and development field. The national budgets allocated to research are distributed on research subjects with well-divers results which are monitored along the entire process. Among all these, the nearly important ones are the entrepreneurial and management culture, their capacities of identifying innovation opportunities [73], to work on a project basis and to identify, diminish or remove the potential risks of the projects [74].

The research and innovation activities include, equally a direct result, the increment of jobs, an economic increment and an increase in the quality of life. The new technologies support the new approach to social problems such as poverty, poor health and environmental deposition or work rubber, since SMEs are supported by a series of national or regional regulations [75], specially designed as political and social run a risk management strategies.

Consequently, the second prepare of hypotheses are explored:

Hypothesis2a.

The turnover of all active enterprises at the national level is determined by the expenditures on innovation performed past SMEs and big enterprises.

Hypothesis2b.

The turnover of all active enterprises at the national level is driven by expenditures on innovation performed by all enterprises.

Hypothesis2c.

The turnover of all active enterprises at the national level is adamant by the expenditures on innovation performed by all SMEs.

iii. Data and Methodology

3.1. Sample Description and Variables

The research sample consisted of business statistics-series–business organisation-demography, over the menstruum 2009–2017, the data source shown by the Romanaian Statistical Yearbook. The selected variables are presented in Table 1.

Consistent with prior studies [2,half-dozen,twenty,32,39,42,48,72], turnover was selected in lodge to take hold of the territorial economic growth, alongside investments [32], firm size [6,28,48,52,72], expenditures on innovation [47,72] and the number of enterprises.

3.two. Econometric Framework

With the purpose to examine the expressed hypotheses, similar to previous studies [2,32,53], we judge ordinary to the lowest degree squares (OLS) regressions. The log–log form is adopted, with MacKinnon–White (HC2) heteroskedasticity-consistent standard errors and covariance. In lodge to ensure the aforementioned society of magnitude, the logarithmic transformation was accomplished for all the selected variables, except the net investments performed past micro-enterprises at the national level (X1B2) due to several zero values. There will be estimated regression equations for each of the settled hypotheses, every bit depicted below.

Model 1 (M1). TY1A is the selected dependent variable that signifies the turnover of all active enterprises at the national level. The independent variables are TX1A1 representing the total gross investments acquired by these companies, alongside TX3A signifying the number of employees. A model of linear regression is built with 2 independent variables, β1, βtwo and βthree representing the parameters of the regression model and εi the disturbance term. The equation of the multiple linear regression is depicted below:

log(TY1A) = β1 + β2*log(TX1A1) + βthree*log(TX3A) + εi.

Model two (M2). TY1A is the chosen predicted variable that depicts the turnover of all the companies at the national level. The explanatory variable is TX1A1 representing the total gross investments performed by these companies. A fix of information with 64 values from 8 regions of development for a catamenia of eight years (2009–2016) is considered. A model of linear regression with a single independent variable is built, where β1 and β2 are the parameters of the regression model and εi the error term. The equation of the model of the univariate linear regression is described beneath:

log(TY1A) = C(1) + βii*log(TX1A1) + εi.

Model iii (M3). TY1A is the elected explained variable that shows the turnover of all the companies at the national level. The predictor variables are TX1B1, TX1C1, TX1D1 and TX1E1 showing the total gross investments performed past the micro, minor, centre-sized and big companies. A model of linear regression with four independent variables is estimated, βone, β2, β3, β4 and β5 existence the parameters of the regression model and εi the error term. The equation of the model of multiple linear regression is shown underneath:

log(TY1A) = βane + β2*log(TX1B1) + βiii*log(TX1C1) + β4*log(TX1D1) + βfive*log(TX1E1) + εi.

Model iv (M4). Y1B is the selected dependent variable that represents the turnover of all the micro-enterprises at the national level. The regressors are X1B2 depicting the net investments performed by these companies, X2B representing the number of agile micro-units and X3B measuring the number of employees. The data serial includes 832 values, respective to the 8 regions of development, regarding 8 years and thirteen sectors of the economy. A model of linear regression is estimated, having 3 independent variables, where βone, βtwo, β3 and β4 depict the parameters of the regression model and εi the disturbance term. The equation of the multiple linear regression model is described below:

log(Y1B) = β1 + β2*log(X1B2) + β3*log(X2B) + βiv*log(X3B) + εi.

Model 5 (M5). Information technology is considered that the turnover at the national level is adamant by the expenditures on innovation performed by companies. It is analyzed based on two size categories: SMEs and large enterprises. TY1A is the chosen regress and that represents the turnover of all the companies at the national level. The independent variables are TX4D and TX4E that catches the expenditures on innovation performed by SMEs and large enterprises. The data serial includes 24 values, respective to the 8 development regions for three years. Yet, in the Romanian Statistical Yearbook, the data regarding expenditures on innovation are reported every two years. A model of linear regression with two contained variables is estimated, βi, βii and β3 showing the parameters of the regression model and εi the disturbance term. The equation of the model of multiple linear regression is represented below:

log(TY1A) = βane + β2*log(TX4E) + β3*log(TX4D) + εi.

Model 6 (M6). It is considered that the turnover at the national level is driven by the total expenditures accomplished by enterprises. TY1A is established as the dependent variable that signifies the turnover of all the companies at the national level. The independent variable is represented by TX4A that measures the expenditures on innovation performed by all companies. A model of linear regression with a single contained variable is estimated, where βone and βii are the parameters of the regression model and εi the error term. The equation of the model of simple linear regression is depicted underneath:

log(TY1A) = βone + βtwo*log(TX4A) + εi.

Model 7 (M7). It is considered that the turnover at the national level is determined by the expenditures on innovation performed by companies. TY1A is acknowledged equally the response variable that catches the turnover of all the companies at the national level. The explanatory variable is TX4E that measures the expenditures on innovation performed by all SMEs. A model of elementary linear regression with a single independent variable is estimated, where β1 and β2 are the parameters of the regression model and εi the disturbance term. The equation of the model of simple linear regression is defined underneath:

log(TY1A) = β1 + βtwo*log(TX4E) + εi.

4. Empirical Findings and Discussion

4.1. Preliminary Assay

The data regarding the total turnover of Romanian enterprises is analyzed further. Tabular array 2 concerns the local active units from industry, structure, merchandise and other services from the eight Romanian development regions.

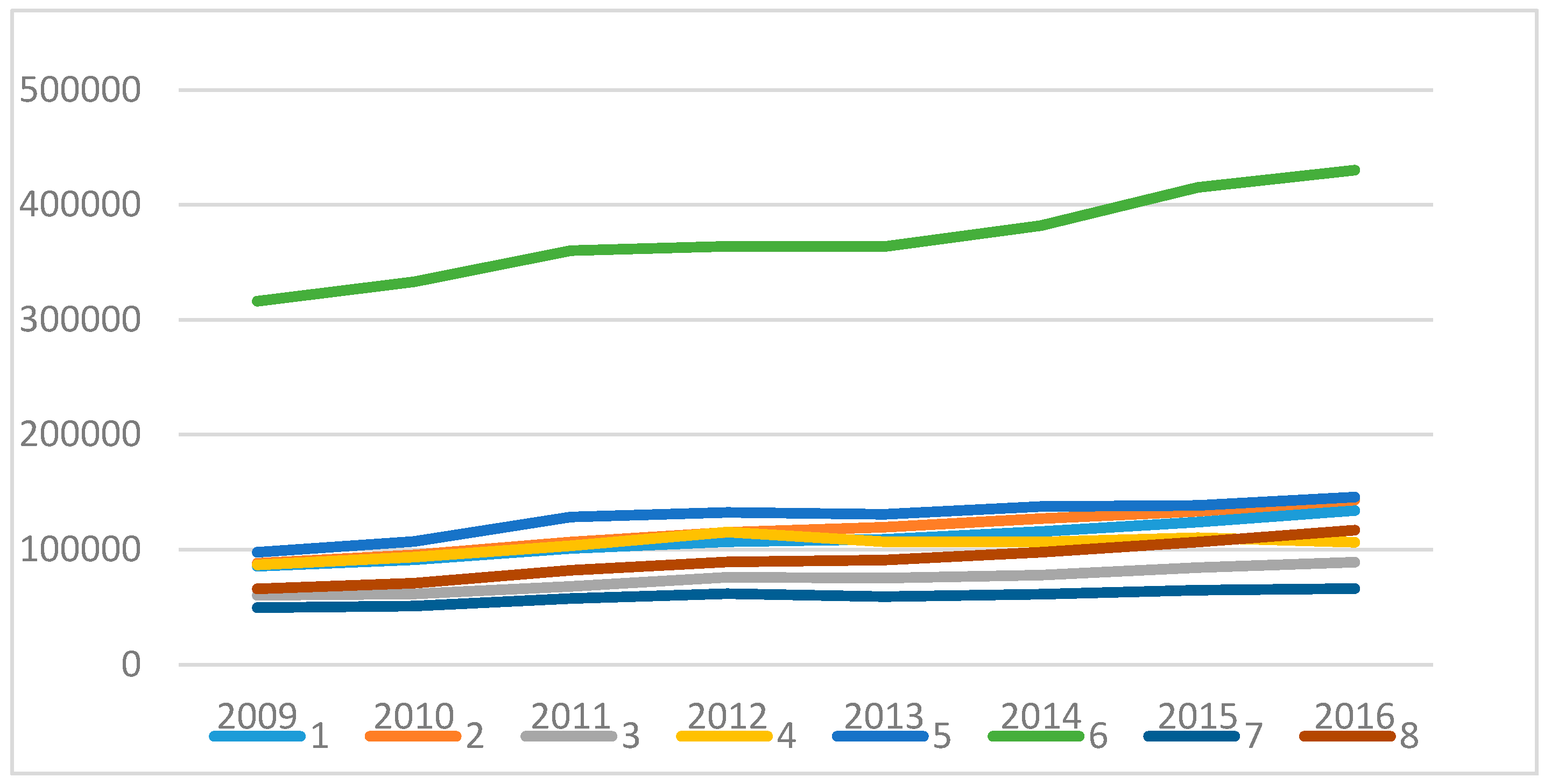

In line with Table ii and Figure 1, we notice that for region number six, Bucharest–Ilfov, the ane that includes the upper-case letter and the neighboring areas, at that place is a superior development level compared to other areas. This may occur probably due to the more attractive business organisation environment, offering both opportunities for new companies and qualified, trained personnel with bully experience in management, amend access to diverse resources, infrastructure, specialists and links with academics.

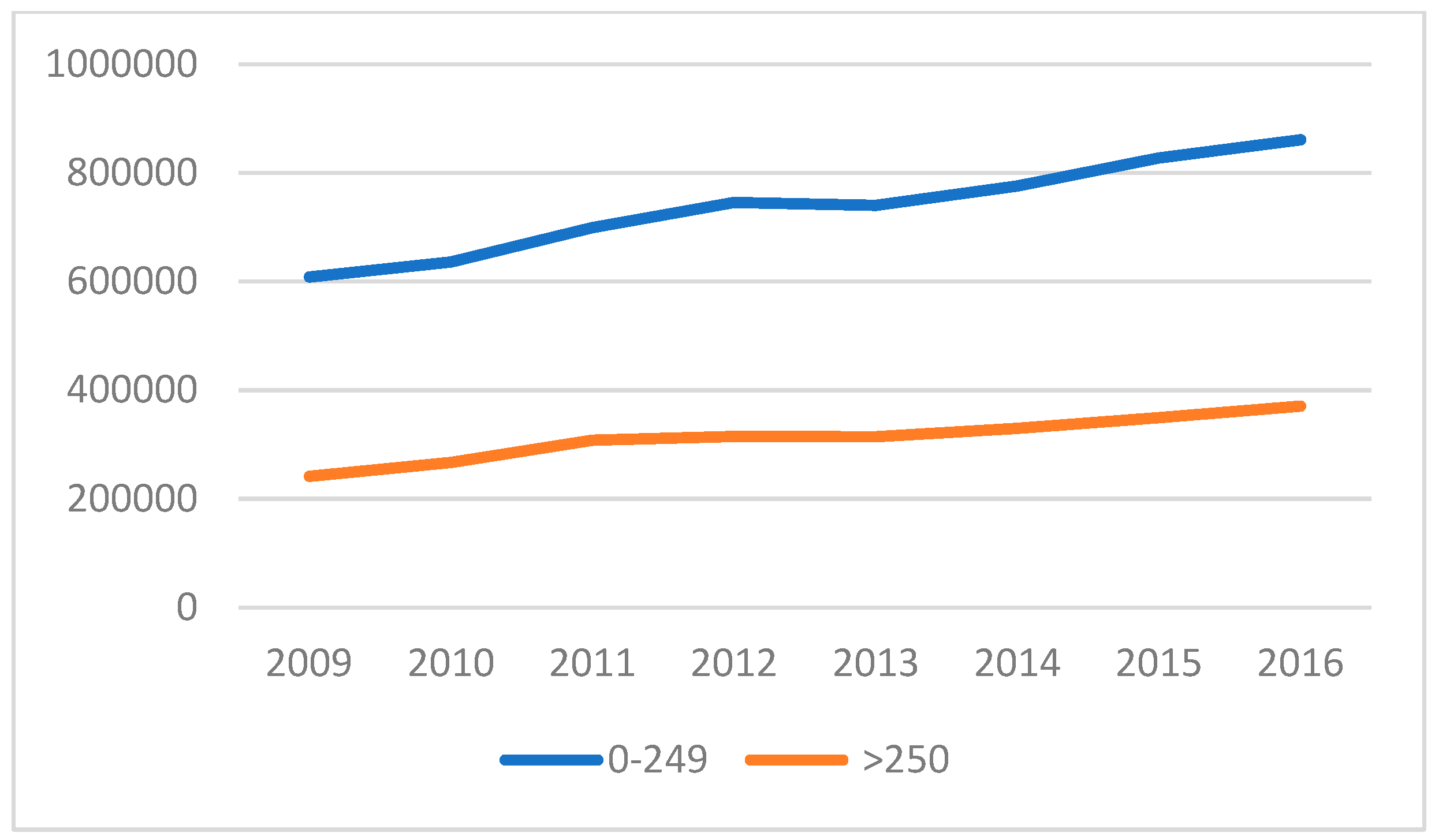

The annual turnover for big, active companies at the national level, and the ones accomplished past SMEs, is reported in Table three, whereas Figure 2 reveals that the SMEs' full turnover exceeds the turnover of large enterprises.

Thus, it is proven that in that location is a greater importance that needs to exist granted to the support and evolution of SMEs, as a pillar of the territorial development, through the governmental, European or regional policies belonging to the local and central administrative policymakers.

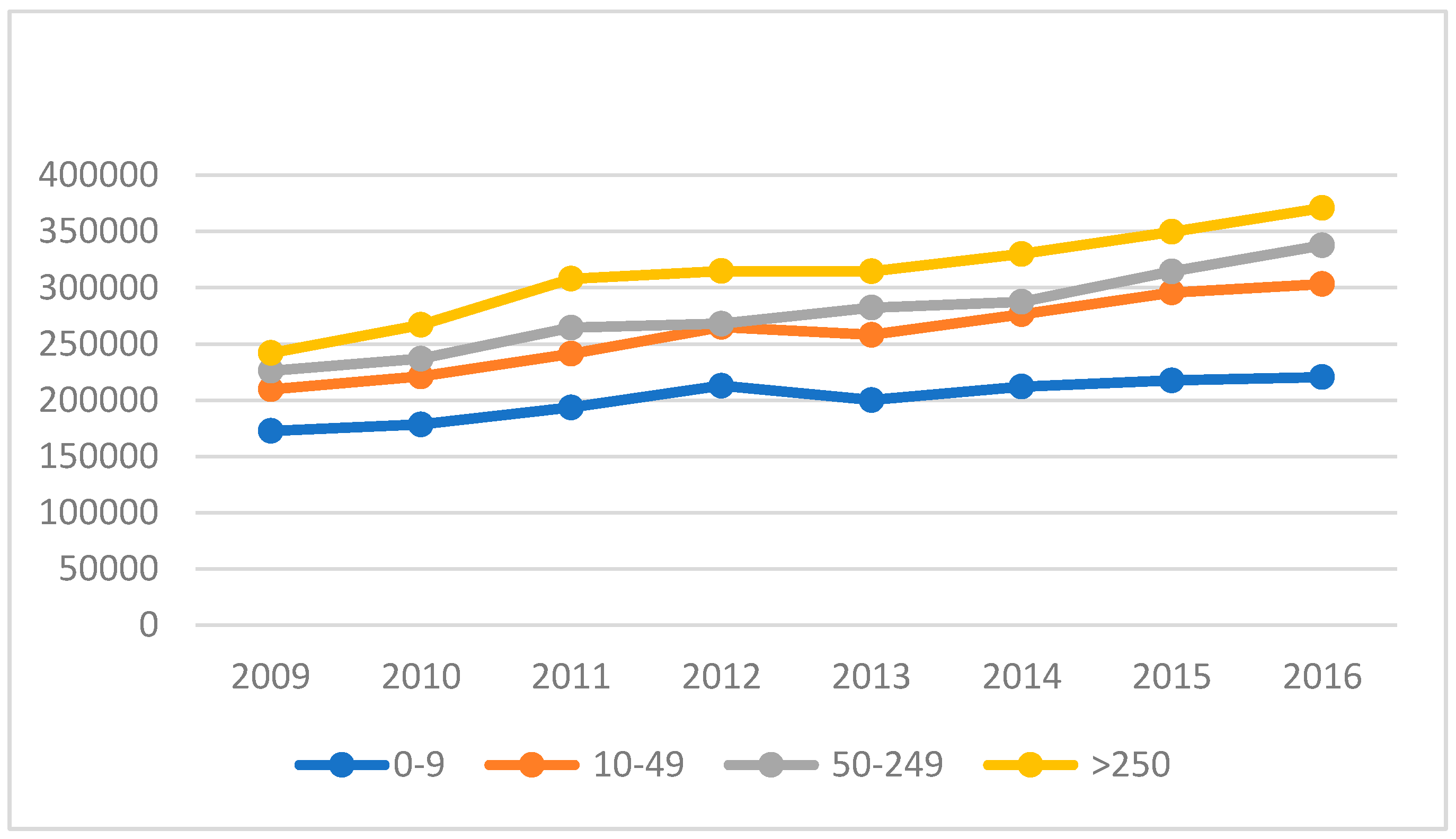

By analyzing the turnover of enterprises of different sizes, as conveyed in Table 4, fifty-fifty if all of them experienced the same upwardly trajectory, Effigy 3 reveals that the large enterprises have a greater value for this indicator. Nevertheless, all of these cumulated information indicate that SMEs may greatly exceed this value (Figure 2).

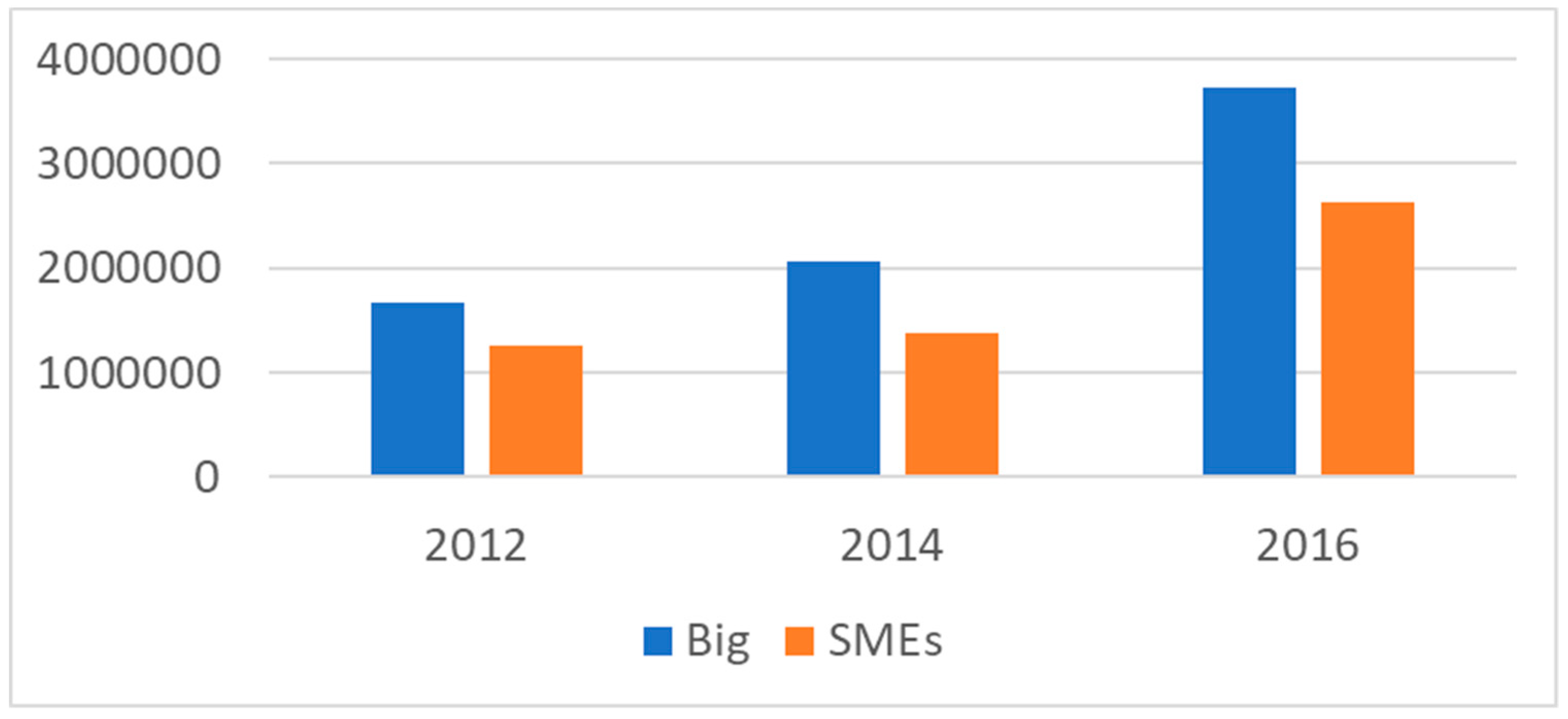

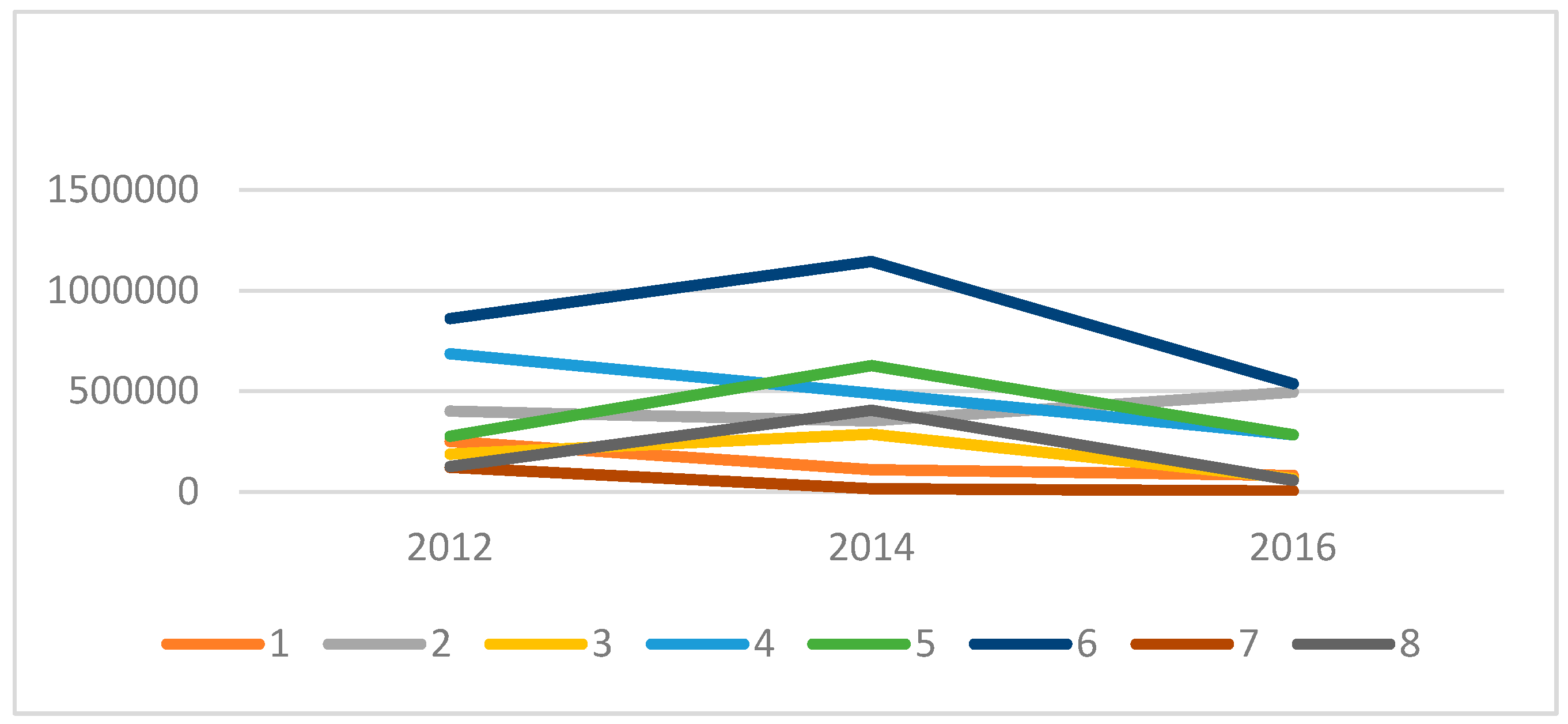

By exploring the expenditures on innovation performed by SMEs and big enterprises in Romania, as showed in Tabular array 5 and Effigy 4, it is noted that, at the national level, the innovation spending related to SMEs follows the increased tendency of big enterprises, even the absolute value is smaller than the one of the big companies. A closer analysis of years and regions of evolution, reported in Tabular array 6 and Figure 5, shows that in Romania, the total innovation of SMEs from the Bucharest–Ilfov region is larger than the innovation registered in the other regions. Thus, it is confirmed that an attractive region, such equally the uppercase city of a state, offers suitable transport infrastructure, business concern opportunities, experience and improve collaboration with the academic and research community, human resource of diverse specializations and a competitive and challenging environment. The innovation of SMEs depends to a large extent on the specificity of the company [77], in close relation to the company's position on the market place and its connection to the market's request. It as well hinges on its organizational strategy and its direction, on the protection offered for different measures of prevention and protection against the risks that may occur especially in the field of investment.

Prior studies show that most of these problems may be recognized and solved through an extensive-learning organizational process. Its features are the capacity to successfully influence the organizational performance of SMEs [78,79], the ability to pb on a competitive advantage [eighty] to a strong performance of the concern model [81] mirrored through the turnover, as well equally to foster social responsibility measures along with development and competitive growth [82]. The organizational capacity of learning may manifest itself via certain actual mechanisms, such every bit experimentation, risk-taking, interaction with the external environment, the dialogue and the participatory decision-making process [83]. It tin can likewise manifest itself through adopting modern high-performance technologies [84] proving the importance of learning over the study of the market [85] and of the clients' choices on a very dynamic actual market [86]. These all contribute to the valuable effect on the performance of SMEs regarding the ecological dynamism [87], of light-green products [88] and of the investments regarding the training and specialization of the human being resource [89].

SMEs' development and their orientation in an extremely dynamic global market are reliant on the educational and continuous preparation process of human resources for new specializations, that may ensure the usage of new high-performance technologies in conditions of high functioning for enterprises [90]. The two atmospheric condition are essentially related as follows: the man resource training limits the usage of new technologies in the field for active companies and even for their management [91]. In response, all these volition create certain conditions regarding the performed investments and innovations of the management teams in general, and of the SMEs in item. The SMEs with a lower charge per unit of bureaucracy, with a greater flexibility and a more rapid capability to adapt to the market requests, may grow, may develop more efficiently through investments and innovation expenditures, in all its forms.

iv.2. Regression Models Outcomes

4.2.1. The Impact of Investments on Territorial Economic Growth

The empirical outcomes of the first regression model are reported in Table 7. The estimated value of the coefficient of determination (R-squared) reveals that the variation of the values of the independent variables (TX1A1 and TX3A) explains the variation of the dependent variable (TY1A) on a ratio of 90.59%. For each i% increase in the value of gross investments (TX1A1), turnover (TY1A) increases past 0.25%. Therefore, the neoclassical theory [51] is supported. Likewise, if the number of employees (TX3A) increases by one per centum, turnover will increase past 1.11%, as in prior studies [6,28]. Hence, Hypothesis 1a is confirmed, the turnover at the national level being determined by the investments performed by companies and past the number of employees.

With reference to the second hypothesis, the empirical estimations are shown in Tabular array 8. The estimated value of the R-squared reveals the fact that the variation of the values of the independent variable (TX1A1) explains the variation of the dependent variable to an extent of 79.69%. If the value of gross investments (TX1A1) rises by i percentage, turnover will increment by 0.77%. Consistent with the results from Table 7, the investments volition determine an intensification of the profitability, consistent with [49]. Thereby, Hypothesis 1b is confirmed, the turnover at the national level being determined by the investments performed by companies.

Further, the enquiry aims to investigate to what extent the turnover of all the companies at the national level is driven by the investments performed by companies, depending on their size (micro, small, medium and big). As regards the third model, the quantitative results are displayed in Tabular array 9.

The estimated value of the R-squared reveals the fact that the simultaneous variation of the values of the independent variables (TX1B1, TX1C1, TX1D1 and TX1E1) explains the variation of the dependent variable (TY1A) to an extent of 92.92%. If the value of investments performed by micro-enterprises (TX1B1), small companies (TX1C1), middle-sized companies (TX1D1) or big companies (TX1E1) increases past one percent, turnover will increase past 0.21%, 0.37%, 0.14% or 0.11%. Hence, Hypothesis 1c is confirmed, the turnover being determined past the investments performed by companies for all types of sizes. The prominence of the SMEs over the evolution and support of the economical growth of a certain land is proved. This reputation is best-selling by EU legislation and regulations, through the government policies that promote the establishing, increase and financing process of SMEs. The consideration of political factors must exist fatigued so as to ensure like shooting fish in a barrel admission of these enterprises to financing resources [17], alongside better and diverse development opportunities. Likewise, SMEs that are flexible due to their size, organization and dynamics are easily adjustable to the market place request. They must wisely adapt their investments to a high implementation level of the technology and to the automation process of all the activities, to ensure work and environment conditions according to modernistic standards, besides the products and processes innovation. All these are attracted and implemented by a modern management that uses techniques, procedures and up-to-appointment programming and command instruments which would ensure the beingness and the evolution of the long-term of the SMEs, in the context of a continuously fluctuating market.

The estimations related to the fourth econometric model are conveyed in Table 10. The estimated value of the R-squared reveals the fact that the variation of the values of the contained variables (X1B2, X2B and X3B) explains the variation of the dependent variable (Y1B) to an extent of 75.92%.

For each i% increase in the number of micro-units (X2B) and the number of employees in a micro-enterprise (X3B), turnover (TY1A) increases past 0.35% and 0.51%, respectively. A one-unit of measurement increase in net investments performed by micro-enterprises (X1B2) will generate an increase in the geometric mean of turnover by 0.06%. Nevertheless, for minor firms, the sales revenues are regularly more appropriate in overcoming liquidity problems than for funding the investment [42]. As such, Hypothesis 1d is confirmed, the turnover of micro-enterprises at the national level being determined by the investments performed past companies, by the number of micro active units and by the number of the employees. All the same, with reference to this category of enterprises, the investments are fifty-fifty more difficult to be implemented because the visitor should access external financing resources.

four.2.2. The Impact of Innovation on Territorial Economic Growth

The outcomes of the fifth regression model are exhibited in Table 11. The estimated value of the R-squared reveals the fact that the simultaneous variation of the values of the independent variables (TX4E and TX4D) explains, to an extent of 59.21%, the variation of the dependent variable (TY1A). For each 1% increment in the value of expenditures on innovation performed by big companies (TX4E), turnover (TY1A) increases by 0.37%. Besides, in the example of SMEs, the relationship between expenditures on innovation and turnover is not statistically pregnant. Unfortunately, in line with Armeanu, Istudor and Lache [38], Romanian SMEs reveal a reduced ability to innovate, aslope their concentration in depression-value-added generating areas, restricted access to financing and poor management. Therefore, Hypothesis 2a is confirmed but for SMEs.

The results regarding the examination of the sixth hypothesis are presented in Tabular array 12. The estimated value of the R-squared reveals the fact that the variation of the contained variable (TX4A) explains, to an extent of 39.01%, the variation of the dependent variable (TY1A). Also, if the value of expenditures on innovation performed by all enterprises increases by one pct, turnover will increment by 0.26%. Consequent with Exposito and Sanchis-Llopis [39], the introduction of product innovation emphasizes a positive bear on on the probability of sales intensification. Hence, Hypothesis 2b is confirmed.

The outcomes of the seventh model are reported in Table 13. The estimated value of the R-squared reveals the fact that the variation of the independent variable (TX4E) explains, to an extent of 57.44%, the variation of the dependent variable (TY1A). Hence, for each ane% increment in the expenditures on innovation performed past big enterprises (TX4E), turnover (TY1A) increases by 0.31%. Hereby, Hypothesis 2c is confirmed. Companies invest in innovation aiming to gather market share, subtract costs and plow out to be more prolific. Since customer requests have become more than specific and competition has amplified, innovation is essential [60].

5. Concluding Remarks and Policy Implications

The electric current study explored the affect of investments and innovation on territorial economic growth, as measured past the turnover, for Romanian business concern statistics serial over the period 2009–2017. By estimating several log–log linear regressions, the empirical findings provide support for a positive impact of investments on territorial economic growth. The relationship was proven both for all active enterprises at the national level and for micro, small, heart and big companies. In the case of innovation-oriented expenditures, our interpretation results testify a positive impact on turnover for all enterprises and large companies, simply a lack of association was established in the case of SMEs. Besides, there was a noticeable positive impact of business firm size on turnover for all active enterprises at the national level, as well every bit for active micro-units. Likewise, the results suggested a positive influence on the number of active micro-units on territorial economic growth.

In our view, this written report has some noteworthy policy implications. The managers should learn from the previous experience of other companies whose success or failure had been investigated so every bit to recognize the factors and relations that led to factual results [92]. These companies will accept to adopt several requirements such equally: A willingness to give up the traditional blazon of management, possible, by identifying and accepting new challenges, building an organizational construction regarding the learning procedure and the adoption process of new technologies along with the innovation involved inside all domains. All these essentially atomic number 82 to management innovation, a segment that is directly related to the organizational facet of the company [93], to the usage of new managerial practices, the practice of so-called management innovators [94]. They should try to combine the ideas gained from diverse studies, analyze and further adapt them to the specific needs of the intended enterprises. All these together class the organizational innovation and carry an of import role regarding the results of innovation [95] aiming at the process and the last products.

In Romania a series of programs of European financial support is bachelor to exist accessed, by SMEs, through certain projects regarding development, the implementation of loftier technologies or the mechanization of some processes, for the educational activity of employees, for the protection of the surround, for the quality assurance in all domains, to provide support for the management efficiency [96]. There are also other types of projects that help the SMEs by offering financing, funding business incubators, stimulating some activities or encourage higher employment, motivating the purchase and the implementation concerning information and communication technologies that grade the cadre of evolution. It is vital to have a bigger fiscal arrangement that is able to support entrepreneurs and the dissimilar stages of the lifecycle of small firms [46]. College levels of economic, financial and institutional expansion are imperative in improving house fiscal restrictions [48].

This study has several restrictions. Possibly the most constraining limitation of this research is emphasized by the selected dataset, collected from the Romanaian Statistical Yearbook. Owning more disaggregated information, namely firm-level data, would allow catching more characteristics such as total assets, house age, labor productivity or internationalization. Given that the heterogeneous aspect of SMEs hinges on the size of a region's economic activity, regional effects intended for decision-making for the viii regions of Romania were not considered. Besides, consistent with Motta and Sharma [28], employing the number of employees as a mensurate towards house size may be challenging inasmuch as the number of employees is driven by the economic size of the company, quality of the firm, option of operational leverage and type of business. As future enquiry avenues, the electric current paper should be developed by exploring the causal relationships between, investments, innovation and territorial economic growth. As well, a sectorial assay may depict another forthcoming direction.

Author Contributions

Conceptualization, Ș.C.G., G.A.B., A.H. and L.Northward.S.; data curation, Ș.C.Thousand., G.A.B., A.H. and L.N.Due south.; formal assay, Ș.C.One thousand., M.A.B., A.H. and L.N.S.; funding conquering, Ș.C.G., M.A.B., A.H. and L.N.S.; investigation, Ș.C.G., K.A.B., A.H. and 50.N.Due south.; methodology, Ș.C.G., Chiliad.A.B., A.H. and Fifty.North.Southward.; project administration, Ș.C.G., M.A.B., A.H. and L.N.S.; resources, Ș.C.M., Grand.A.B., A.H. and 50.N.S.; software, Ș.C.Thou., M.A.B., A.H. and L.Northward.Southward.; supervision, Ș.C.G., Chiliad.A.B., A.H. and L.Northward.S.; validation, Ș.C.Yard., M.A.B., A.H. and L.Northward.S.; visualization, Ș.C.Thousand., M.A.B., A.H. and L.N.South.; writing—original draft, Ș.C.Chiliad., M.A.B., A.H. and L.N.S.; Writing—review and editing, Ș.C.Chiliad., M.A.B., A.H. and L.N.S. All authors have read and agreed to the published version of the manuscript.

Funding

This inquiry received no external funding.

Conflicts of Interest

The authors declare no conflict of interest.

References

- Obi, J.; Ibidunni, A.S.; Tolulope, A.; Olokundun, Chiliad.A.; Amaihian, A.B.; Borishade, T.T.; Fred, P. Contribution of small and medium enterprises to economical development: Evidence from a transiting economy. Data Cursory 2018, xviii, 835–839. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ndiaye, North.; Razak, L.A.; Nagayev, R.; Ng, A. Demystifying small and medium enterprises' (SMEs) performance in emerging and developing economies. Borsa Istanb. Rev. 2018, xviii, 269–281. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Commission, E. Entrepreneurship and Small and Medium-Sized Enterprises (SMEs). Available online: https://ec.europa.eu/growth/smes_en (accessed on 12 Baronial 2019).

- European Parliament. Fact Sheets on the European union; European Parliament: Bruxelles, Belgium, 2019.

- Perez-Gomez, P.; Arbelo-Perez, Yard.; Arbelo, A. Profit efficiency and its determinants in small and medium-sized enterprises in Kingdom of spain. BRQ Bus. Res. Q. 2018, 21, 238–250. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dowling, M.; O′Gorman, C.; Puncheva, P.; Vanwalleghem, D. Trust and SME attitudes towards disinterestedness financing across Europe. J. Earth Bus. 2019, 54. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Committee of the European Communities. Advice from the Commission to the Quango, the European Parliament, the European Economic and Social Committee and the Commission of the Regions. In COM(2008); 394 last; Commission of the European Communities: Brussels, Belgium, 2008. [Google Scholar]

- Yoshino, Northward.; Taghizadeh-Hesary, F. Optimal credit guarantee ratio for small and medium-sized enterprises' financing: Show from Asia. Econ. Anal. Policy 2019, 62, 342–356. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Luo, P.F.; Wang, H.Yard.; Yang, Z.J. Investment and financing for SMEs with a partial guarantee and spring risk. Eur. J. Oper. Res. 2016, 249, 1161–1168. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Winfred, A., Jr. Pro-poor economic growth: Role of small and medium sized enterprises. J. Asian Econ. 2006, 17, 35–xl. [Google Scholar]

- European Commission. Advice from the Commission to the European Parliament, the Council, the European Economic and Social Committee and the Commission of the Regions; In COM(2012) 573 final; European Commission: Brussels, Kingdom of belgium, 2012. [Google Scholar]

- European Parliament. European Parliament Resolution of 15 June 2010 on Customs Innovation Policy in a Irresolute World (2009/2227(INI)); European Parliament: Bruxelles, Belgium, 2010.

- European Parliament. European Parliament Resolution of ix March 2011 on an Industrial Policy for the Globalised Era (2010/2095(INI)); In 2012/C 199 Due east/16; European Parliament: Bruxelles, Belgium, 2011.

- European Parliament. European Parliament Resolution of 23 October 2012 on Small and Medium Size Enterprises (SMEs): Competitiveness and Business Opportunities (2012/2042(INI)); In 2014/C 68 E/06; European Parliament: Bruxelles, Belgium, 2012.

- European Parliament. European Parliament Resolution of 15 January 2014 on Reindustrialising Europe to Promote Competitiveness and Sustainability (2013/2006(INI)); In 2016/C 482/xiii; European Parliament: Bruxelles, Kingdom of belgium, 2014.

- European Parliament. European Parliament Resolution of 5July 2017 on Building an Ambitious Eu Industrial Strategy as a Strategic Priority for Growth, Employment and Innovation in Europe; In 2017/2732(RSP); European Parliament: Bruxelles, Belgium, 2017.

- European Parliament. European Parliament Resolution of 15 September 2016 on Access to Finance for SMEs and Increasing the Diversity of SME Funding in a Capital Markets Marriage (2016/2032(INI)); In 2016/2032(INI); European Parliament: Bruxelles, Kingdom of belgium, 2016.

- European Commission. Communication from the Commission to the European Parliament, the Quango, the European Economic and Social Commission and the Committee of the Regions; In COM(2018) 2 final; European Committee: Brussels, Belgium, 2018. [Google Scholar]

- Directorate-General for Research and Innovation (European Committee). Mid-Term Review of the Contractual Public Private Partnerships (cPPPs) under Horizon 2020; European Committee: Brussels, Belgium, 2017. [Google Scholar]

- Gonzalez-Loureiro, M.; Pita-Castelo, J. A model for assessing the contribution of innovative SMEs to economic growth: The intangible arroyo. Econ. Lett 2012, 116, 312–315. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Popescu, Northward.E. Entrepreneurship and SMEs Innovation in Romania. In Proceedings of the 21st International Economical Conference of Sibiu 2014, Iecs 2014 Prospects of Economic Recovery in a Volatile International Context: Major Obstacles, Initiatives and Projects, Sibiu, Romania, sixteen–17 May 2014; Volume sixteen, pp. 512–520. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Porter, M.E. Competitive Advantage, Agglomeration Economies, and Regional Policy. Int. Reg. Sci. Rev. 1996, 19, 85–90. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Porter, M.E. Customers Who Viewed Competitive Advantage: Creating and Sustaining Superior Performance, 1st ed.; Gratuitous Press: New York, NY, The states, 1998. [Google Scholar]

- European Commission. Sixth Periodic Study on the Social and Economic Situation and Evolution of Regions in the European Wedlock; European Commission: Brussels, Kingdom of belgium, 1999. [Google Scholar]

- Gardiner, B. Competitiveness Indicators for Europe—Audit, Database Construction and Assay. Reg. Stud. Assoc. Int. Conf. 2003. Available online: http://citeseerx.ist.psu.edu/viewdoc/download?doi=10.1.i.197.8343andrep=rep1andtype=pdf (accessed on 24 August 2019).

- Camagni, R. On the concept of territorial competitiveness: Audio or misleading? Urban Stud. 2002, 39, 2395–2411. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Myslimi, M.; Krisdela, Grand. Impact of SMEs in economic growth in Albania. Eur. J. Sustain. Dev. 2016, 5, 151–158. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Motta, V.; Sharma, A. Lending technologies and access to finance for SMEs in the hospitality industry. Int. J. Hosp. Manag. 2019, in press. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Woźniak, M.; Duda, J.; Gąsior, A.; Bernat, T. Relations of Gdp growth and development of SMEs in Poland. In Proceedings of the 23rd International Conference on Knowledge-Based and Intelligent Data and Technology Systems, Budapest, Hungary, iv–6 September 2019. [Google Scholar]

- Hasan, I.; Jackowicz, K.; Kowalewski, O.; Kozlowski, L. Practise local banking market place structures matter for SME financing and operation? New prove from an emerging economy. J. Banking company Financ. 2017, 79, 142–158. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sipa, One thousand.; Gorzen-Mitka, I.; Skibinski, A. Determinants of Competitiveness of Small Enterprises: Polish Perspective. In Proceedings of the 22nd International Economic Briefing of Sibiu 2015, Iecs 2015 Economic Prospects in the Context of Growing Global and Regional Interdependencies, Sibiu, Romania, 15–16 May 2015; Book 27, pp. 445–453. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jackowicz, One thousand.; Kozlowski, L. Social ties betwixt SME managers and banking concern employees: Financial consequences vs. SME managers' perceptions. Emerg. Mark. Rev. 2019, twoscore. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Oncioiu, I.; Capusneanu, Due south.; Turkes, M.C.; Topor, D.I.; Constantin, D.M.O.; Marin-Pantelescu, A.; Hint, 1000.S. The Sustainability of Romanaian SMEs and Their Interest in the Circular Economy. Sustainable (Basel) 2018, 10, 2761. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Neagu, C. The importance and role of small and medium-sized businesses. Theor. Appl. Econ. 2016, 23, 331–338. [Google Scholar]

- Belu, M.G.; Popa, I.; Filip, R. The Bear upon of Globalisation on Small-scale and Medium Enterprises: The Romanian Feel. Rom. Econ. J. 2018, 21, 42–51. [Google Scholar]

- Nistor, I.E.; Popescu, D.-R. Romanaian SMEs Financing Options:An Empirical Analysis. Financ. Chall. Future 2013, 1, 12–21. [Google Scholar]

- Aceleanu, M.I.; Traşcă, D.50.; Şerban, A.C. The role of pocket-size and medium enterprises in improving employment and in the post-crisis resumption of economic growth in Romania. Theor. Appl. Econ. 2014, 1, 87–102. [Google Scholar]

- Armeanu, D.; Istudor, N.; Lache, L. The role of smes in assessing the contribution of entrepreneurship to GDP in the romanaian business surround. Amfiteatru Econ. 2015, 17, 195–211. [Google Scholar]

- Exposito, A.; Sanchis-Llopis, J.A. The human relationship between types of innovation and SMEs' operation: A multi-dimensional empirical assessment. Eurasian Bus. Rev. 2019, 9, 115–135. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tahir, H.M.; Razak, Due north.A.; Rentah, F. The Contributions of Small and Medium Enterprises (SME's) on Malaysian Economical Growth: A Sectoral Analysis. In Proceedings of the 7th International Conference on Kansei Technology and Emotion Research 2018, Kuching, Sarawak, Malaysia, nineteen–22 March 2018; Springer: Berlin, Germany, 2018. [Google Scholar]

- Ghassibe, M.; Appendino, M.; Mahmoudi, S.E. SME Financial Inclusion for Sustained Growth in the Center East and Central Asia. In IMF Working Papers; International Monetary Fund (International monetary fund): Washington, DC, U.s., 2019. [Google Scholar]

- Mendes, S.; Serrasqueiro, Z.; Nunes, P.K. Investment determinants of immature and one-time Portuguese SMEs: A quantile approach. BRQ Motorcoach. Res. Q. 2014, 17, 279–291. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gupta, J.; Gregoriou, A. Touch on of market-based finance on SMEs failure. Econ. Model. 2018, 69, xiii–25. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Trinh, L.Q.; Doan, H.T.T. Internationalization and the growth of Vietnamese micro, small-scale, and medium sized enterprises: Show from panel quantile regressions. J. Asian Econ. 2018, 55, 71–83. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chinembiri, T. Exploring the Role of Small and Medium Enterprises in Economic Evolution: Some Policy Considerations for Republic of zimbabwe; In ZEPARU Working Newspaper Series; (ZEPARU); Zimbabwe Economic Policy Analysis and Research Unit of measurement (ZEPARU): Harare, Republic of zimbabwe, 2011. [Google Scholar]

- Wellalage, N.H.; Fernandez, V. Innovation and SME finance: Prove from developing countries. Int. Rev. Financ. Anal. 2019, 66. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Apanasovich, North.; Heras, H.A.; Parrilli, M.D. The impact of business organization innovation modes on SME innovation operation in post-Soviet transition economies: The case of Belarus. Technovation 2016, 57–58, 30–40. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ullah, B. Financial constraints, corruption, and SME growth in transition economies. Q. Rev. Econ. Financ. 2019, in press. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kersten, R.; Harms, J.; Liket, One thousand.; Maas, Thou. Small Firms, large Impact? A systematic review of the SME Finance Literature. World Dev. 2017, 97, 330–348. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chenery, H.B. Overcapacity and the Acceleration Principle. Econometrica 1952, twenty, 1–28. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chirinko, R.Due south. Concern Fixed Investment Spending—Modeling Strategies, Empirical Results, and Policy Implications. J. Econ. Lit. 1993, 31, 1875–1911. [Google Scholar]

- Baker, H.Grand.; Kumar, Due south.; Rao, P. Financing preferences and practices of Indian SMEs. Glob. Financ. J. 2017, in press. [Google Scholar]

- Asai, Y. Why do small and medium enterprises (SMEs) demand holding liability insurance? J. Bank Financ. 2019, 106, 298–304. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, Y. What are the biggest obstacles to growth of SMEs in developing countries?—An empirical prove from an enterprise survey. Borsa Istanb. Rev. 2016, sixteen, 167–176. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Agostini, 50.; Filippini, R. Organizational and managerial challenges in the path toward Industry 4.0. Eur. J. Innov. Manag. 2019, 22, 406–421. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mlozi, Southward. A Post Hoc Analysis of LearningOrientation–Innovation–Performancein the Hospitality Manufacture. Acad. Tur. 2017, 10, 27–41. [Google Scholar]

- Cohen, Due west.M.; Levinthal, D.A. Absorptive-Capacity—A New Perspective on Learning and Innovation. Adm. Sci. Q. 1990, 35, 128–152. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hunter, One thousand.K.; William, D.P., Jr. Sales Engineering science Orientation, Information Effectiveness, and Sales Operation. J. Pers. Sell. Sales Manag. 2006, 26, 95–113. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Damanpour, F. The dynamics of the adoption of production and process innovations in organizations. J. Manag. Stud. 2001, 38, 45–65. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- OECD. Measuring Innovation. In A New Perspective; OECD: Paris, France, 2010. [Google Scholar]

- Cousins, J. MBA ASAP Marketing 2.0: Principles and Exercise in the Digital Age Paperback; Independently Published, 2018; Available online: https://www.amazon.com/MBA-ASAP-Marketing-2-0-Principles/dp/1717884334 (accessed on 24 August 2019).

- Wignaraja, G. Competitiveness Strategy in Developing Countries. A Manual for Policy Analysis, 1st ed.; Routledge: London, UK, 2003. [Google Scholar]

- Barney, J. Firm Resources and Sustained Competitive Advantage. J. Manag. 1991, 17, 99–120. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bang, A.; Cleemann, C.M.; Bramming, P. How to create concern value in the knowledge economy Accelerating thoughts of Peter, F. Drucker. Manag. Decis. 2010, 48, 616–627. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Baron, R.A.; Markman, G.D. Beyond social capital: The part of entrepreneurs' social competence in their financial success. J. Coach. Ventur. 2003, xviii, 41–lx. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Clarke, J. Revitalizing Entrepreneurship: How Visual Symbols are Used in Entrepreneurial Performances. J. Manag. Stud. 2011, 48, 1365–1391. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Prokop, D.; Huggins, R.; Bristow, G. The survival of bookish spinoff companies: An empirical study of key determinants. Int. Pocket-size Bus. J. 2019, 37, 502–535. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bergek, A.; Norrman, C. Incubator all-time practice: A framework. Technovation 2008, 28, xx–28. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Akbar, Y.; Balboni, B.; Bortoluzzi, G.; Dikova, D.; Tracogna, A. Disentangling resource and fashion escalation in the context of emerging markets. Evidence from a sample of manufacturing SMEs. J. Int. Manag. 2018, 24, 257–270. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Guvernul României. Ordonanța nr. 8/1997 privind stimularea cercetării-dezvoltării și inovării. 1997. Available online: http://www.cdep.ro/pls/legis/legis_pck.htp_act?ida=13234 (accessed on 24 Baronial 2019).

- OECD. Oslo Manual. Guidelines for Collecting and Interpreting Innovation Data; OECD: Paris, France, 2005. [Google Scholar]

- Saridakis, G.; Idris, B.; Hansen, J.Thousand.; Dana, L.P. SMEs' internationalisation: When does innovation matter? J. Bus. Res. 2019, 96, 250–263. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Guan, H.J.; Zhang, Z.; Zhao, A.W.; Jia, J.Y.; Guan, S. Enquiry on Innovation Behavior and Functioning of New Generation Entrepreneur Based on Grounded Theory. Sustainable (Basel) 2019, 11, 2883. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Botezatu, M.A. Insight Into Project Adventure Management. J. Inf. Syst. Oper. Manag. 2016, x, 137–150. [Google Scholar]

- Kitching, J. Regulatory reform as risk management: Why governments redesign micro company legal obligations. Int. Small Double-decker. J. 2019, 37, 395–416. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- National Institute of Statistics. Statistical Yearbooks of Romania. Bachelor online: http://www.insse.ro/cms/en/content/statistical-yearbooks-romania (accessed on 12 Baronial 2019).

- Dodgson, One thousand. Innovation in firms. Oxf. Rev. Econ. Policy 2017, 33, 85–100. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gomes, G.; Wojahn, R.M. Organizational learning capability, innovation and performance: Study in small and medium-sized enterprises (SMES). Rev. Adm. 2017, 52, 163–175. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kosgei, C.N.; Maru, C.50. Learning orientation and innovativeness of pocket-size and micro-enterprises. Int. J. Small Bus. Entrep. Res. 2015, 3, 1–10. [Google Scholar]

- Calantone, R.J.; Cavusgil, S.T.; Zhao, Y.S. Learning orientation, firm innovation capability, and firm performance. Ind. Mark. Manag. 2002, 31, 515–524. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pang, C.Westward.; Wang, Q.; Li, Y.; Duan, G. Integrative adequacy, business concern model innovation and performance: Contingent upshot of business strategy. Eur. J. Innov. Manag. 2019, 22, 541–561. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ratnawati, T.; Soetjipto, B.E.; Murwani, F.D.; Wahyono, H. The Role of SMEs' Innovation and Learning Orientation in Mediating the Effect of CSR Programme on SMEs' Operation and Competitive Advantage. Glob. Passenger vehicle. Rev. 2018, 19, S21–S38. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Alegre, J.; Chiva, R. Assessing the affect of organizational learning adequacy on production innovation performance: An empirical test. Technovation 2008, 28, 315–326. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Morrison, A.; Pietrobelli, C.; Rabellotti, R. Global Value Chains and Technological Capabilities: A Framework to Study Learning and Innovation in Developing Countries. Oxf. Dev. Stud. 2008, 36, 36–58. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Keskin, H. Market place orientation, learning orientation, and innovation capabilities in SMEs. Eur. J. Innov. Manag. 2006, 9, 396–417. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Salavou, H. Do Customer and Engineering Orientations Influence Product Innovativeness in SMEs? Some New Show from Greece. J. Mark. Manag. 2005, 21, 307–338. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hou, B.J.; Hong, J.; Zhu, K.J.; Zhou, Y. Paternalistic leadership and innovation: The moderating effect of environmental dynamism. Eur. J. Innov. Manag. 2019, 22, 562–582. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tariq, A.; Badir, Y.; Chonglerttham, S. Green innovation and operation: Moderation analyses from Thailand. Eur. J. Innov. Manag. 2019, 22, 446–467. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhao, Y.X.; Thompson, P. Investments in managerial human being capital: Explanations from prospect and regulatory focus theories. Int. Modest Double-decker. J. 2019, 37, 365–394. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mavondo, F.T.; Chimhanzi, J.; Stewart, J. Learning orientation and market orientation. Eur. J. Marking. 2005, 39, 1235–1263. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sirelli, G. Innovation and firm performance. In Proceedings of the Conference Innovation and Enterprise Creation: Statistics and Indicators, Sophia Antipolis, French republic, 23–24 November 2000. [Google Scholar]

- Bacon-Gerasymenko, Five. When practise organisations learn from successful experiences? The case of venture majuscule firms. Int. Small Bus. J. 2019, 37, 450–472. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Khosravi, P.; Newton, C.; Rezvani, A. Management innovation: A systematic review and meta-analysis of past decades of research. Eur. Manag. J. 2019, in press. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Birkinshaw, J.; Hamel, 1000.; Mol, Thou. Management Innovation; In AIM Working Paper Series: 021-July-2005; Schoolhouse, L.B., Ed.; Advanced Institute of Direction Research: London, UK, 2005. [Google Scholar]

- Anzola-Roman, P.; Bayona-Saez, C.; Garcia-Marco, T. Organizational innovation, internal RandD and externally sourced innovation practices: Effects on technological innovation outcomes. J. Jitney. Res. 2018, 91, 233–247. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Botezatu, Thousand.A.; Pirnau, C.; Bother, R.Chiliad.C. A Mod Quality Balls Organisation—Condition and Back up to an Efficient Management. Tem J. 2019, 8, 125–131. [Google Scholar]

Figure 1. The total turnover of the offset companies from the eight developed regions. Source: Authors' processing from the Romanian Annual Statistical Yearbook 2010–2017 [76].

Figure 1. The total turnover of the first companies from the eight developed regions. Source: Authors' processing from the Romanian Annual Statistical Yearbook 2010–2017 [76].

Figure ii. The turnover of SMEs (0–249 employees) and of big enterprises. Source: Authors' processing from the Romanaian Annual Statistical Yearbook 2010–2017 [76].

Figure two. The turnover of SMEs (0–249 employees) and of large enterprises. Source: Authors' processing from the Romanian Annual Statistical Yearbook 2010–2017 [76].

Figure 3. Turnover of enterprises regarding the size category. Source: Authors' processing from the Romanian Almanac Statistical Yearbook 2010–2017 [76].

Figure iii. Turnover of enterprises regarding the size category. Source: Authors' processing from the Romanian Annual Statistical Yearbook 2010–2017 [76].

Effigy 4. The value of expenditures on the innovation of SMEs and big enterprises. Source: Authors' processing from the Romanian Annual Statistical Yearbook 2010–2017 [76].

Effigy 4. The value of expenditures on the innovation of SMEs and big enterprises. Source: Authors' processing from the Romanian Almanac Statistical Yearbook 2010–2017 [76].

Figure 5. Total expenditures on innovation for the enterprises in the eight regions of development. Source: Authors' processing from the Romanian Almanac Statistical Yearbook 2010–2017 [76].

Figure 5. Total expenditures on innovation for the enterprises in the eight regions of development. Source: Authors' processing from the Romanian Almanac Statistical Yearbook 2010–2017 [76].

Table ane. Variables' description.

Table i. Variables' description.

| Variables | Definitions |

|---|---|

| Variables regarding business turnover (Dependent Variables) | |

| TY1A | The turnover of all active enterprises at the national level |

| Y1B | The turnover of all the micro-enterprises at the national level |

| Variables regarding investments (Explanatory Variables) | |

| TX1A1 | Total gross investments obtained by all active enterprises at the national level |

| TX1B1 | Full gross investments performed by the micro companies |

| TX1C1 | Total gross investments performed by the small companies |

| TX1D1 | Total gross investments performed by the heart-sized companies |

| TX1E1 | Full gross investments performed by the big companies |

| X1B2 | Net investments performed by micro-enterprises |

| Variables regarding expenditures on innovation (Explanatory Variables) | |

| TX4A | Expenditures on innovation performed by all enterprises |

| TX4D | Expenditures on innovation performed by SMEs |

| TX4E | Expenditures on innovation performed past big enterprises |

| Variables regarding firm size (Explanatory Variables) | |

| TX3A | The number of employees out of all active enterprises at the national level |

| X3B | The number of employees out of active micro-units |

| Variables regarding the number of enterprises | |

| X2B | The number of agile micro-units |

Table 2. Total turnover for the active local units from manufacture, construction, trade and other services.

Table two. Total turnover for the active local units from manufacture, construction, merchandise and other services.

| Region | 2009 | 2010 | 2011 | 2012 | 2013 | 2014 | 2015 | 2016 |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| ane North-West | 85,673 | 91,222 | 101,068 | 106,958 | 10,8911 | 115,831 | 124,021 | 134,251 |

| 2 Center | 88,253 | 95,354 | 106,679 | 114,973 | 119,574 | 126,904 | 133,324 | 143,313 |

| 3 North-East | threescore,414 | 61,355 | 67,979 | 75,897 | 75,251 | 77,896 | 84,512 | 89,131 |

| 4 South-Due east | 86,943 | 93,476 | 103,380 | 115,446 | 106,792 | 106,701 | 110,370 | 106,377 |

| five South-Muntenia | 97,848 | 107,136 | 128,467 | 132,425 | 130,652 | 137,503 | 138,421 | 145,959 |

| 6 Bucharest–Ilfov | 316,201 | 332,956 | 360,042 | 363,868 | 363,665 | 381,902 | 415,115 | 430,203 |

| 7 South-W Oltenia | 49,527 | 50,953 | 57,426 | 61,734 | 59,110 | 61,177 | 64,697 | 66,159 |

| 8 Westward | 65,975 | 70,786 | 82,110 | 89,207 | 91,037 | 97,804 | 106,706 | 117,095 |

Tabular array 3. The turnover of active companies, minor and medium enterprises (SMEs) and large enterprises (mil Lei).

Table iii. The turnover of active companies, minor and medium enterprises (SMEs) and big enterprises (mil Lei).

| Year/No. of Employees | 0–9 | x–49 | fifty–249 | >250 |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| 2009 | 172,783 | 209,784 | 226,239 | 242,028 |

| 2010 | 178,450 | 221,111 | 236,806 | 266,871 |

| 2011 | 193,513 | 241,214 | 264,461 | 307,963 |

| 2012 | 212,861 | 264,998 | 267,928 | 314,721 |

| 2013 | 200,138 | 258,106 | 282,285 | 314,464 |

| 2014 | 212,025 | 276,365 | 287,391 | 329,936 |

| 2015 | 217,517 | 295,635 | 314,397 | 349,618 |

| 2016 | 220,570 | 303,257 | 337,667 | 370,994 |

Table 4. The turnover of active companies and the size categories (mil Lei).

Table 4. The turnover of active companies and the size categories (mil Lei).

| Year | SMEs (0–249) | Big Companies (>250) |

|---|---|---|

| 2009 | 608,806 | 242,028 |

| 2010 | 636,367 | 266,871 |

| 2011 | 699,188 | 307,963 |

| 2012 | 745,787 | 314,721 |

| 2013 | 740,529 | 314,464 |

| 2014 | 775,781 | 329,936 |

| 2015 | 827,549 | 349,618 |

| 2016 | 861,494 | 370,994 |

Tabular array 5. Expenditures on innovation of SMEs and big enterprises (mil Lei).

Table 5. Expenditures on innovation of SMEs and big enterprises (mil Lei).

| Year | Big | SMEs |

|---|---|---|

| 2012 | 1,663,447 | ane,253,844 |

| 2014 | ii,068,974 | ane,369,763 |

| 2016 | three,732,421 | 2,623,607 |

Table vi. Expenditures on innovation within active enterprises depending on regions (mil Lei).

Tabular array half-dozen. Expenditures on innovation within active enterprises depending on regions (mil Lei).

| Region | 2012 | 2014 | 2016 |

|---|---|---|---|

| ane North-Westward | 251,952 | 111,085 | 82,354 |

| two Middle | 401,308 | 353,020 | 496,385 |

| three Due north-East | 188,403 | 287,744 | 66,920 |

| four South-Eastward | 686,340 | 490,651 | 284,162 |

| 5 South-Muntenia | 277,680 | 628,358 | 283,633 |

| 6 Bucharest–Ilfov | 861,600 | ane,145,411 | 537,984 |

| 7 S-West Oltenia | 123,233 | xv,789 | 4912 |

| 8 West | 126,775 | 406,679 | 57,815 |

Tabular array 7. Estimated parameters of the multiple linear regression model M1 by using the method of least squares.

Table 7. Estimated parameters of the multiple linear regression model M1 by using the method of least squares.

| Variable | Coefficient | Std. Error | t-Statistic | Prob. |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| C | −five.198040 | 1.723701 | −iii.015628 | 0.0037 |

| log(TX1A1) | 0.254622 | 0.135583 | one.877976 | 0.0652 |

| log(TX3A) | 1.105328 | 0.225105 | 4.910274 | 0.0000 |

| R-squared | 0.905874 | Hateful dependent var | xi.61481 | |

| Adjusted R-squared | 0.902788 | Southward.D. dependent var | 0.532504 | |

| S.E. of regression | 0.166028 | Akaike info criterion | −0.707575 | |

| Sum squared resid | i.681492 | Schwarz criterion | −0.606377 | |

| Log likelihood | 25.64239 | Hannan–Quinn criter. | −0.667708 | |

| F-statistic | 293.5348 | Durbin–Watson stat | 1.015572 | |

| Prob(F-statistic) | 0.000000 | Wald F-statistic | 648.6972 | |

| Prob(Wald F-statistic) | 0.000000 | |||

Tabular array 8. Estimated parameters of the simple linear regression model M2 past using the method of to the lowest degree squares.

Table 8. Estimated parameters of the simple linear regression model M2 by using the method of least squares.

| Variable | Coefficient | Std. Mistake | t-Statistic | Prob. |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| C | 4.452171 | 0.683106 | half dozen.517543 | 0.0000 |

| log(TX1A1) | 0.768108 | 0.074703 | x.28216 | 0.0000 |

| R-squared | 0.796887 | Hateful dependent var | 11.61481 | |

| Adjusted R-squared | 0.793611 | S.D. dependent var | 0.532504 | |

| South.Eastward. of regression | 0.241917 | Akaike info criterion | 0.030305 | |

| Sum squared resid | 3.628470 | Schwarz benchmark | 0.097770 | |

| Log likelihood | ane.030236 | Hannan–Quinn criter. | 0.056883 | |

| F-statistic | 243.2494 | Durbin–Watson stat | 1.441618 | |

| Prob(F-statistic) | 0.000000 | Wald F-statistic | 105.7228 | |

| Prob(Wald F-statistic) | 0.000000 | |||

Table ix. Estimated parameters of the multiple linear regression model M3 by using the method of to the lowest degree squares.

Table nine. Estimated parameters of the multiple linear regression model M3 by using the method of least squares.

| Variable | Coefficient | Std. Error | t-Statistic | Prob. |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| C | 5.173465 | 0.240976 | 21.46883 | 0.0000 |

| log(TX1B1) | 0.211263 | 0.052112 | 4.054010 | 0.0001 |

| log(TX1C1) | 0.372942 | 0.084366 | 4.420517 | 0.0000 |

| log(TX1D1) | 0.143356 | 0.084269 | ane.701164 | 0.0942 |

| log(TX1E1) | 0.109920 | 0.051485 | ii.134995 | 0.0369 |

| R-squared | 0.929221 | Mean dependent var | 11.61481 | |

| Adjusted R-squared | 0.924422 | Southward.D. dependent var | 0.532504 | |

| Due south.E. of regression | 0.146393 | Akaike info criterion | −0.930141 | |

| Sum squared resid | i.264421 | Schwarz criterion | −0.761479 | |

| Log likelihood | 34.76452 | Hannan–Quinn criter. | −0.863697 | |

| F-statistic | 193.6448 | Durbin–Watson stat | one.378223 | |

| Prob(F-statistic) | 0.000000 | Wald F-statistic | 433.4057 | |

| Prob(Wald F-statistic) | 0.000000 | |||

Table 10. Estimated parameters of the multiple linear regression model M4 by using the method of least squares.

Table ten. Estimated parameters of the multiple linear regression model M4 past using the method of least squares.

| Variable | Coefficient | Std. Error | t-Statistic | Prob. |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| C | −0.572733 | 0.199315 | −2.873508 | 0.0042 |

| X1B2 | 0.000609 | 0.000151 | four.020901 | 0.0001 |

| log(X2B) | 0.350974 | 0.047841 | 7.336311 | 0.0000 |

| log(X3B) | 0.507031 | 0.050006 | x.13947 | 0.0000 |

| R-squared | 0.759192 | Hateful dependent var | 6.146454 | |

| Adjusted R-squared | 0.758319 | S.D. dependent var | 1.689388 | |

| Southward.E. of regression | 0.830521 | Akaike info criterion | 2.471268 | |

| Sum squared resid | 571.1249 | Schwarz benchmark | ii.493979 | |

| Log likelihood | −1024.047 | Hannan–Quinn criter. | ii.479976 | |

| F-statistic | 870.1407 | Durbin–Watson stat | 0.371520 | |

| Prob(F-statistic) | 0.000000 | Wald F-statistic | 538.1923 | |

| Prob(Wald F-statistic) | 0.000000 | |||

Tabular array xi. Estimated parameters of the multiple linear regression model M5 by using the method of least squares.

Table 11. Estimated parameters of the multiple linear regression model M5 by using the method of least squares.

| Variable | Coefficient | Std. Error | t-Statistic | Prob. |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| C | 8.513681 | 0.645311 | 13.19313 | 0.0000 |

| log(TX4D) | −0.078573 | 0.075360 | −1.042647 | 0.3090 |

| log(TX4E) | 0.369872 | 0.092168 | 4.013022 | 0.0006 |

| R-squared | 0.592076 | Mean dependent var | 11.70371 | |

| Adapted R-squared | 0.553226 | Due south.D. dependent var | 0.520231 | |

| S.Due east. of regression | 0.347729 | Akaike info criterion | 0.841681 | |

| Sum squared resid | 2.539221 | Schwarz criterion | 0.988937 | |

| Log likelihood | −7.100167 | Hannan–Quinn criter. | 0.880748 | |

| F-statistic | 15.24007 | Durbin–Watson stat | 1.142976 | |

| Prob(F-statistic) | 0.000081 | Wald F-statistic | 13.00972 | |

| Prob(Wald F-statistic) | 0.000211 | |||

Table 12. Estimated parameters of the simple linear regression model M6 by using the method of to the lowest degree squares.

Table 12. Estimated parameters of the unproblematic linear regression model M6 by using the method of least squares.

| Variable | Coefficient | Std. Mistake | t-Statistic | Prob. |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| C | 8.564310 | 0.896656 | 9.551389 | 0.0000 |

| log(TX4A) | 0.256394 | 0.075632 | 3.390020 | 0.0026 |

| R-squared | 0.390104 | Hateful dependent var | xi.70371 | |

| Adjusted R-squared | 0.362382 | Southward.D. dependent var | 0.520231 | |

| S.E. of regression | 0.415410 | Akaike info criterion | 1.160553 | |

| Sum squared resid | 3.796439 | Schwarz criterion | 1.258725 | |

| Log likelihood | −eleven.92664 | Hannan–Quinn criter. | one.186598 | |

| F-statistic | 14.07174 | Durbin–Watson stat | 1.684148 | |

| Prob(F-statistic) | 0.001104 | Wald F-statistic | 11.49224 | |

| Prob(Wald F-statistic) | 0.002633 | |||

Table 13. Estimated parameters of the unproblematic linear regression model M7 by using the method of least squares.

Tabular array 13. Estimated parameters of the simple linear regression model M7 by using the method of least squares.

| Variable | Coefficient | Std. Error | t-Statistic | Prob. |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| C | 8.292346 | 0.739660 | 11.21103 | 0.0000 |

| log(TX4E) | 0.306904 | 0.068674 | iv.468970 | 0.0002 |

| R-squared | 0.574391 | Mean dependent var | 11.70371 | |

| Adjusted R-squared | 0.555045 | Southward.D. dependent var | 0.520231 | |

| S.E. of regression | 0.347020 | Akaike info benchmark | 0.800788 | |

| Sum squared resid | two.649306 | Schwarz benchmark | 0.898959 | |

| Log likelihood | −7.609451 | Hannan–Quinn criter. | 0.826832 | |

| F-statistic | 29.69058 | Durbin–Watson stat | ane.083840 | |

| Prob(F-statistic) | 0.000018 | Wald F-statistic | 19.97170 | |

| Prob(Wald F-statistic) | 0.000192 | |||